Article created in partnership with the DOEN Foundation.

Lusanga is a village about 570 kilometres from Kinshasa, in the Kwilu Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a population of roughly 15,000. Its history reflects the ecological devastation brought about during the colonial era.

Like much of the former Bandundu province, northeast of Kinshasa in the DRC, the village of Lusanga was once surrounded by dense tropical forests. Century-old trees and a rich biodiversity once sustained both ecological balance and the livelihoods of local communities.

As early as 1911, Huileries du Congo Belge (HCB), a subsidiary of the Anglo-Dutch conglomerate Unilever, seized vast tracts of land in the Belgian Congo to establish oil palm plantations, clearing forests and compelling local communities to abandon their traditional farming practices. This exploitation, sustained by a brutal regime of forced labour sanctioned by the Belgian colonial administration, devastated the environment and upended established ways of life.

Belgian colonial policies, driven by European industrial demands, prioritised resource extraction through vast land concessions to companies such as HCB, and the enforced monoculture of oil palms. This approach not only depleted the territory’s soils, once home to dense tropical forests, but also dismantled ancestral ways of life by coercing indigenous communities into exploitative labour regimes under the constant threat of violence and imprisonment.

From the arrival of HCB in 1911 through to the 1950s, Lusanga and its surroundings were systematically transformed from a vibrant haven of biodiversity into a green desert. Today, the landscape bears no trace of its former richness; only a monotonous expanse of oil palms and wild grasses remains. In many areas, these palms stand like frozen sentinels, silent witnesses to decades of reckless resource exploitation and the brutal disfigurement of ecosystems.

Art - a powerful medium to envision a different future

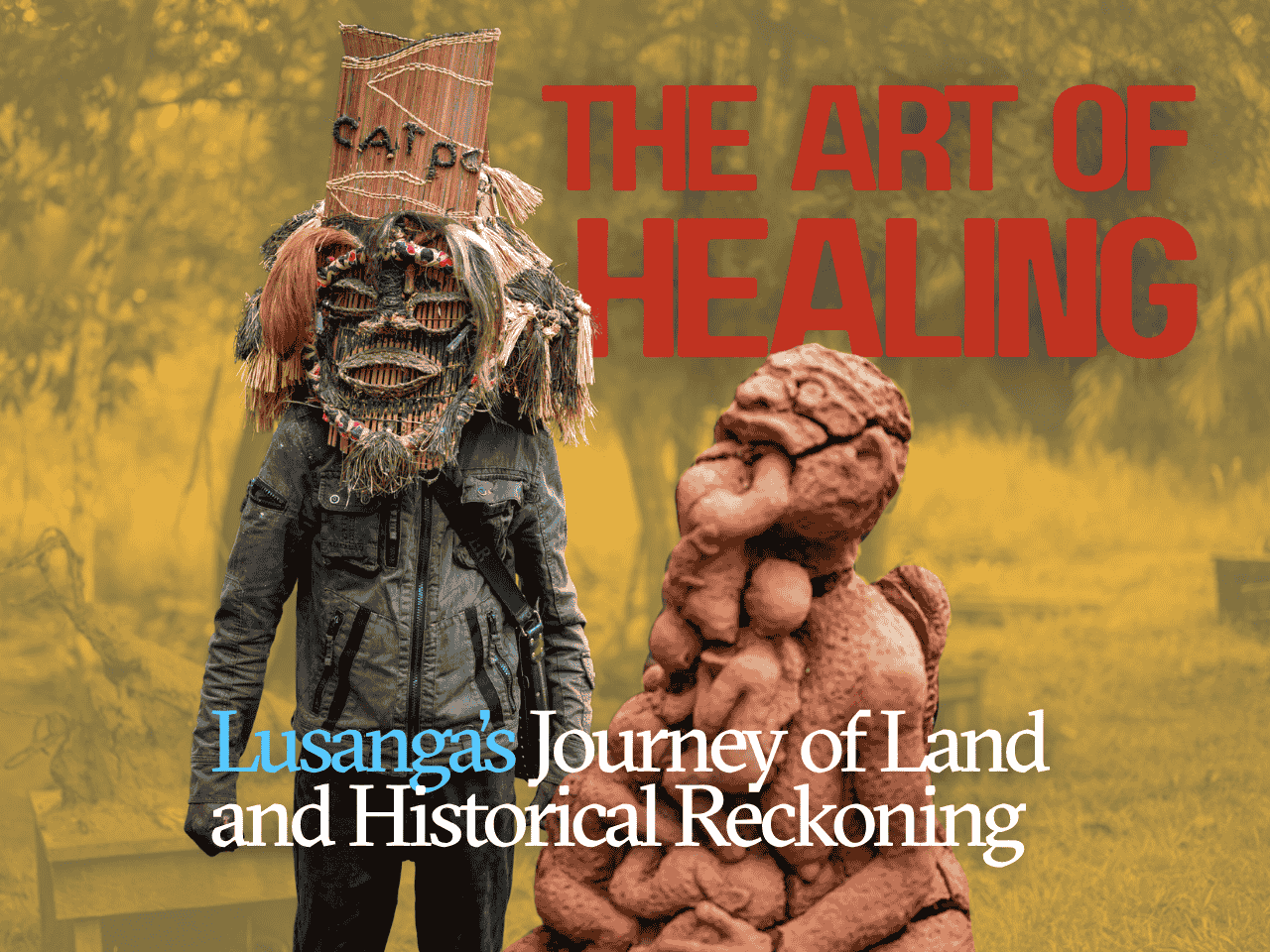

However, over the past decade hope has been rekindled in Lusanga. In 2014, motivated by a desire to revive local artistic and cultural heritage, which had long been dismissed and denigrated as “fetishes” by Belgian colonists, a group of self-taught artists from the city of Kikwit and neighbouring villages, founded the Cercle d’Art des Travailleurs de Plantation Congolaise (CATPC), or the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League.

This initiative emerged not in isolation, but from a collective of Congolese plantation workers and Kinshasa-based artists. They yearned to reclaim agency and artistic expression in a region scarred by decades of colonial exploitation and environmental degradation linked to the very plantations that had shaped their lives. René Ngongo, a prominent Congolese environmental activist and founder of Greenpeace Congo, played a crucial role in bringing the plantation workers together and connecting them with Kinshasa-based artists. Their art became a powerful medium to remember and critique historical injustices, as well as to envision and actively work towards a different future for Lusanga and its people.

The collective of Congolese artists behind this ambitious project focuses on restoring degraded lands through a combination of reforestation, agroforestry and artistic creation. Their goal is to enhance local food security while reclaiming cultural narratives and heritage. The history of Lusanga is one example among many African territories that have experienced similar ecological devastation. However, this initiative demonstrates that ecological and cultural restoration is possible when approached inclusively and sustainably.

“Our greatest wealth is our history”

CATPC is repurposing reclaimed land to develop a pioneering model called ‘post-plantation,’ offering an alternative to the destructive monocultures of traditional plantations. This approach restores life to impoverished soils while providing local communities with sustainable livelihoods and contributing to a more equitable future. Leveraging art as a catalyst for positive change, CATPC confronts colonial legacies that have historically undermined local cultures. The collective critically engages with colonial memory, transforming art into a tool for cultural revitalisation and the reclamation of identity.

“Our greatest wealth is our history,” asserts Alphonse Bukumba of the CATPC communications department. The collective draws its inspiration from oral traditions, relying on the stories passed down through generations to shape contemporary artistic expression. Their sculptures, paintings, and performances transcend mere aesthetics; they articulate the sufferings of the past and the aspirations of the present. Through these works, the artists denounce deforestation, imposed monocultures and the historical exploitation of Congolese plantation workers.

"Our ancestors made art their way, even in suffering," explains Athanas Kindendi, an artist and father of seven. "Today, we use our art to convey a new message. It’s time to preserve our land and leave a positive legacy for our children," adds the determined fifty-something. To pass on this artistic legacy to future generations by decolonising the plantation through thoughtful reflection and acts of restoration, CATPC created the Luyalu School (which means ‘solidarity’ in the local Kikongo language) in 2022. At the centre, adult artist-planters guide nearly 100 local children in artistic expression grounded in ancestral wisdom and collective identity.

The reforestation project led by CATPC extends beyond an ecological initiative; it forms part of a broader transformation of the prevailing economic model. Rather than relying solely on monocultural oil palm cultivation, the artist’s collective invests in efforts that promote polyculture at its Lusanga site while exploring alternative agricultural approaches. Traditional techniques are being revived with the guidance of environmental experts, agronomists, and committed artists. The project emphasises the pursuit of agriculture that is both more resilient and respectful of nature. To date, local residents have reforested over 400 hectares of previously degraded land.

"Our commitment is clear. We only make arable land available to those who commit to cultivating it with respect for the environment. For example, no slash-and-burn agriculture is allowed on our sites. Sustainable agriculture is the only way to preserve our soils, our forests, and the futures of generations to come," states Sara Mapaya, an agronomist at CATPC.

Alongside this, the provocative artworks produced by CATPC have reached the international stage, exhibited in prominent institutions such as the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, the Netherlands), the Venice Biennale (Italy), SCCA Tamale (Ghana), and the Sculpture Center (New York, USA). These sculptures, originally modelled in clay in Lusanga, are digitally scanned and reproduced through 3D printing, and then cast in cacao, sugar and, crucially, palm oil - all raw materials directly sourced from the very plantations that have shaped the region’s history and landscape.

The exhibition of these works worldwide, which are products of colonial-era exploitation, serves a dual purpose. They not only raise critical public awareness about the enduring impacts of colonisation, environmental degradation and human suffering, they also generate vital revenue which is directly reinvested in local land restoration projects and the development of the ‘post-plantation’ in Lusanga.

Most museums were built with revenue from plantations

Alphonse Bukumba highlights a forgotten and uncomfortable truth about the legacy of colonialism that deeply permeates the Western art world. He points out that many prominent museums were financially established through wealth generated by colonial-era plantations, a reality the world has largely overlooked.

“Most museums were built with revenue from plantations. Sadly, the world has forgotten this reality and does not take it into account. Through our actions, we want to remind museums of the need to take care,” Bukumba explained. This economic dynamic, in which art created from the raw materials of colonial exploitation is exhibited and sold in the same institutions that profited from that exploitation, offers both the committed artist-farmers of CATPC and the wider local community, a sustainable and empowering alternative to the enduring poverty inherited from the past.

Take the example of the white cube. The artist Renzo Martens, whose methods have drawn criticism for his controversial approach to depicting poverty, built a "white cube" at the CATPC project in Lusanga. This bold gesture does more than expose the colonial wealth that funded Western museums; it directly confronts the contradictions of the white cube itself. The core tension lies in the clash between two ideas of value: art’s seemingly universal beauty, displayed in clean, neutral spaces, and the land’s harsh, physical reality and its history of exploitation.

The “white cube,” despite its apparent purity, inadvertently exposes how art’s supposed higher value can rest upon the very ground that embodies immense suffering and resource extraction. This forces a difficult reckoning between idealised art and the devastating real-world impact on the land.

For the people of Lusanga, this green renaissance transcends mere environmental restoration. It signifies a symbolic reconquest of land stolen by colonial powers, a reclaiming of suppressed memory and the forging of a self-determined future. For generations, local inhabitants were subjected to the brutal realities of exploited labour on plantations, stripped of autonomy and denied control over their own destiny. Today, through the powerful synergy of their art and the sustainable practices of agroforestry, local people are gradually taking back control of their ancestral territory and rewriting their own narrative.

Chief Kindashi Kinoni of the neighbouring Kianga village articulates this sentiment: "The ravaging of our lands has stripped us of our essential survival resources. The impoverished soils do not produce enough food. Hunters do not bring back much. The CATPC project gives us a glimmer of hope for the return of the forests that once sustained us. Already, unemployment has decreased, as many of our brothers work from time to time on the planting project, which we support as much as we can."

This ambitious project proves that, beyond simple landscape restoration, it is possible to reinvent inclusive economic models rooted in respect for ancestral knowledge and the power of collective creativity.

Healing the wounds inflicted on this territory and its people

All in all, the arduous struggle led by the Congolese Plantation Workers’ Art Circle, though undeniably promising, remains far from fully delivering on its commitments to long-suffering local communities. The crucial first phase focuses on reforesting vast areas that were converted into colonial monoculture prairies. Consequently, while agroforestry is central, intensive agriculture aimed at immediate food security has not yet played a dominant role in the project. Nevertheless, hope now appears tangible. Sparked by this grassroots initiative, the project aims to plant 2,000 hectares of biodiverse forest by 2030 and to thoughtfully extend its transformative potential to neighbouring villages.

This grand aspiration reflects CATPC's unwavering commitment to boldly heal the lasting wounds inflicted on this territory on a vast scale. With every tree planted, every work of art created and every empowering community initiative launched, the resilient people of Lusanga are collectively writing a new chapter in their long and complex history, one of a renaissance where the healing power of nature and the enduring strength of culture unite to rebuild a self-determined future.

The Lusanga initiative presents an alternative model for regions worldwide where deforestation, unchecked industrialisation and the erosion of ancestral knowledge have left lasting scars. By emphasising participatory reforestation, sustainable economic practices and culture as a catalyst for change, the initiative demonstrates that restoring nature also restores the connection between people and their land.

Artist Daniel Muvunzi from Lusanga rendered this truth poetically: “Like the tilapia that releases its fry out of its mouth after the enemy has passed, this post-plantation mother releases the artists from within her. We are no longer in the time of colonisation. Now, we are living decolonisation. We are at ease, we are free, we plant trees. Now we have forests, and we are at peace.”

A key factor for Lusanga’s future success will be the continued involvement of its inhabitants. Wherever ecosystems have been ravaged, whether in the Amazon, Southeast Asia, or parts of Africa, restoring the power of local populations to act is essential.

The clarity of this mission was captured by Lusanga artist Antanase Kidendi: “Our ancestors initiated us into this art. We draw our inspirations from their lived experiences, not from elsewhere or learned from foreigners. In the end, our inspiration is ancestral inspiration.”

The example of CATPC demonstrates that meaningful environmental preservation extends far beyond agricultural practices alone. It encompasses the vital transmission of collective memory and the articulation of lived experience. By transforming their painful history of colonial exploitation into compelling and resolute works of art, the artists of Lusanga offer a powerful reminder that ecological struggle is inseparably linked to the pursuit of identity and social justice.

Music, painting, theatre, storytelling—these profoundly resonant mediums give voice to affected communities and engage a broader audience in the urgent imperative of restoring both the delicate balance of nature and the dignity of its people.

However, while community involvement and empowerment are essential, the ultimate success of an ecological restoration project also depends critically on the formation of strong partnerships that extend beyond local boundaries. Non-governmental actors, research institutions, responsive governments enacting supportive policies and ethical businesses committed to sustainability must align their diverse capacities. They are called upon to provide the financial, technical, and logistical support necessary for local initiatives to scale their impact effectively.

In the urgent mission to restore the planet’s degraded ecosystems, we must strategically deploy tools that advance both environmental recovery and fundamental fairness. This entails advocating for ecological compensation funds that hold polluters accountable, alongside robust reforestation programmes supported by voluntary contributions from conscious consumers and corporations. Equally essential are credible labels that transparently certify the responsible management of vital natural resources.

These are not just policies; they are concrete steps towards not only mending broken landscapes but also advancing the cause of climate justice. The degradation of the environment and the deep-seated inequities within our societies are inextricably linked. By acknowledging this interconnectedness, we can forge a path towards a future where both people and the planet can thrive. A future rooted in responsibility, restoration and a shared commitment to healing.

The White Cube: A Paradoxical Stage for Decolonial Agency

In the art world, the White Cube has long symbolised neutrality. But for the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (CATPC), it’s a radical, controversial space. It is a powerful metaphor for their struggle: a seemingly neutral stage that simultaneously facilitates their empowerment and highlights their dependency.

While the Lusanga White Cube symbolises a direct reclamation of stolen land and narrative, its existence, and the funding for land buybacks by former plantation workers, depends on art sales within the very Western art institutions that profited from colonial extraction. This creates a challenging dynamic where the pursuit of autonomy is funded by, and thus inevitably tied to, the systems of power it seeks to dismantle.

The White Cube, therefore, becomes a site where liberation is both performed and constrained, revealing the ongoing entanglement of decolonial work with the very structures it seeks to resist.

By ZAM reporter

Lisez la version originale en français ici.

This article is created in partnership with the DOEN Foundation. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of the DOEN Foundation.