Article created in partnership with the DOEN Foundation.

It’s early in the morning in Commune 3 of Bamako, Mali, and there’s a buzz in the neighbourhood. A group of young people are busy preparing the open space, which is sometimes used for events. To prevent dust from rising, the young girls carefully sprinkle water on the ground before sweeping the area clean in preparation for the ceremony to mark the return of Les Praticables (The Platforms), a biennial theatre event that had, over the years, become associated with the neighbourhood.

In a country that has endured a multidimensional conflict lasting more than a decade, challenges still loom large for Malian artists. There is reduced mobility of performances due to security concerns, a loss of funding linked to the departure of certain NGOs that supported cultural and artistic projects, not to mention a certain silence surrounding the handling of sensitive issues related to the country’s political situation by artists.

For some, Les Praticables might have appeared to be a new artistic form introduced to the neighbourhood by its initiator, Lamine Diarra—but for me, it wasn’t new.

I remember entering our small neighbourhood town hall to see the very first play of my life, as a little girl, alongside my sisters. Going to the theatre or cinema in the early 1980s was a highlight event, one we had to prepare for in advance. At that age, it wasn’t so much the topics being addressed that captivated us, but rather the antics of the actors that made us laugh until our stomachs hurt.

Beyond the comedic scenes, the actors always managed to deliver a message to the audience. Just like the stories told by my grandmother, theatre for us was a form of moral and life teachings. In those days, the topics addressed had their origins in folktales and popular stories. I remember a performance called the “Nyogolon,”, a form of popular theatre where the actors mixed dancing, acrobatics and singing. It wasn’t uncommon for them to involve the audience during the performances and underlying the performance there was always a social message.

This is what made the “Nyogolon,” a powerful communication tool for local communities and it was part of a wider public communication tradition that was commonplace in advertisements, safety messages and health and agricultural campaigns. This art form still exists and is still used to convey messages to local communities. Plays are part of almost every public ceremony in Mali. Between speeches or musical interludes, important social messages are conveyed to the audience. The national television channel allocates airtime for plays, often presented as sketches. This exposure has helped launch the careers of many actors, propelling them into the global arts scene.

A striking campaign from my childhood, on the dangers of using skin-lightening products

I still remember a striking campaign from my childhood that raised awareness about the dangers of using skin-lightening products. It became widely popular for its originality—the play featured puppets instead of actors, a first at the time. Its influence still lingers: a song from the play, "Dimogo ba gnekelen," which means "big one-eyed fly," is still used to refer to fans of skin whitening. Even today, you might hear neighbourhood children humming the tune whenever they come across a “Tchatcho,” a Malian term for someone who uses skin-lightening products. Despite the enduring impact of colonialism and modernity, this indigenous form of African theatre—rooted in oral traditions and folktales—continues to thrive, thanks to the dedication of directors, playwrights, actors and the communities that embrace it. It endures because it reflects their lived realities.

Theatre is embedded in people's consciousness

For most Malians, theatre represents a valuable heritage that offers a space for learning and personal development, as well as an important means of gaining insight into their culture and society. The importance of theatre in our education is no longer up for debate. We have learned much of our local culture through theatre. Theatre has helped many children develop their ability to express themselves and has given them a sense of confidence. There are still school programmes that use theatre as a pedagogical method to communicate societal behaviours, history, children's rights, disease awareness and other sensitive topics.

Theatre is embedded in people's consciousness. It is rare to meet a Malian without a memory related to a play, whether as an actor or a spectator. Therefore, I was not surprised by the enthusiasm of the Bamako Coura neighbourhood towards this venture. Kuma So is the name of the organisation running the Les Praticables project, and from the beginning, they had placed their bet on a winning horse.

By collaborating with the community, Les Praticables was guaranteed success, especially with the decision to partner with the women of the neighbourhood. This is how I came to learn about the Bamako-Coura Women's Association, which plays a bridging role in interactions with the community.

Founded during the first edition of Les Praticables, this association proved that the involvement of the local women of Bamako Coura can bring about significant changes within the community. To learn more, I decided to go to the source and speak to the president of the group. After two days of discussions, Kadiatou Sy, the young woman I was to meet, finally gave me an appointment at her home to discuss the Les Praticables Women’s Association, which she has led since 2017.

Around forty years old, she is married and a mother of four children. She works at the Urban Mutual Betting company in Bamako, commonly known as PMU. It was after a long day of work that she would receive me at her home, in her living room, surrounded by a group of children watching a football match. I understood that her reluctance to do the interview was due to a great shyness that she could hardly hide. How, then, did someone so reserved manage to lead a large association with many members in the neighbourhood?

Made up of around one hundred people, the Bamako-Coura Women's Association is at the heart of Les Praticables, handling all logistics, which involves a great deal of cooking alongside the organisation of neighbourhood shows. Before turning to theatre, Kadiatou Sy’s women’s group had started informally as a welfare collective of twenty women, commonly known in Mali’s popular language as a "Tontine."

A "Tontine" is a weekly gathering organized to allow stay-at-home mothers, most of whom were often unemployed, to contribute a small sum, which is then circulated among the members in a round-robin fashion. In essence, it is a savings and investment plan that helps the women equip themselves with the basics of daily living, such as kitchen utensils, household linens and soap. A resident learned about the women’s weekly meetings and connected them with the Les Praticables team and the rest is history. The women were easily persuaded to collaborate with the theatre group because Lamine, the founder, was a child of the neighbourhood whom they had seen grow up into a role model.

Just like Kadiatou Sy, I was also a resident of the neighbourhood. Like many others, I had been surprised to see the women involved in an area that typically carries a controversial reputation in Malian society. Isn't it often said in Mali that a person with an eccentric or exuberant attitude is "behaving like a theatre actor"?

What drew these women together around a sector they usually kept a distance from? Theatre was not among the careers a parent wished for their child. But attitudes in Bamako-Coura were changing and I had witnessed these women encouraging their children to occasionally get involved in the world of the arts. It was evident that Les Praticables had given the women of Bamako-Coura agency as the faces of change in the community. They seemed to be the first true believers and understood that artistic initiatives are not just money-making ventures—a stereotype often associated with locally-based projects supported by grant money.

The security situation hangs over Mali like a dark cloud, and even noble artistic projects like Les Praticables are sometimes criticised as an escape from reality. The stereotypes persist.

"Here’s another artist who wants to amuse himself with useless stories."

"He won’t come and fill his pockets at our expense again."

"The Whites have given him a lot of money, but he will surely keep it all for himself."

Kadiatou told me how they try to counter this thinking: "We explain to the people that Les Praticables performances are not there to enrich the population, but to bring about concrete changes within the community through theatre".

Theatre is one of the only vehicles that challenge the status quo of Malian cultural society

The women know this because theatre is one of the only vehicles that challenges the status quo of Malian cultural society. Since its creation, the performances have touched on controversial issues directly affecting the community. Indeed, during one of the weekly meetings that I attended, the topic of early marriages—still a significant cultural issue in Malian society—was discussed.

The legal minimum age for marriage in Mali is 18 for both sexes; however, early marriages are still prevalent. In practice, many girls are married off at younger ages due to societal and familial pressures. Many of the women admitted that they had never questioned the consequences of early marriage, but through theatre, they came to realise the hidden and often darker aspects that befall young girls shackled by this tradition.

Convinced that theatre could bring about change in their communities, the women of Bamako Coura saw it as an opportunity to express themselves differently in a society where their voices are often unheard. The association’s meetings are often organised in alternating homes to create a safe space for women to discuss taboo topics, free from judgment. They are hopeful, but also realistic, knowing that change can, after all, be a very slow process.

In a patriarchal society like Mali, where the most important decisions for the community are made by men, other levers are necessary to change the tide. The majority of the adult male population remains indifferent to the arts sector. During the various Les Praticables performances, I observed the men; they were often present as honorary guests, resource people, or simple spectators—always in a position of distance. In the eyes of these heads of families, the arts are not highly regarded, and very few would choose it as a career path for their children. Their presence is, therefore, mostly limited to that of figurants.

Although some of the men are consistent in their commitment to the performances, they still set limits for themselves. It would, therefore, in my opinion, be impossible for Les Praticables' performances to break certain social barriers without the involvement of those who make the real decisions in the community. Fortunately, the younger generation offered some hope and I observed with great relief the enthusiasm they had regarding the activities.

We return to that memorable day when the small neighbourhood performance space made of packed earth had been cleaned and watered to keep the dust down. The night before the ceremony began, large plates of spaghetti Bolognese had been prepared for the occasion.

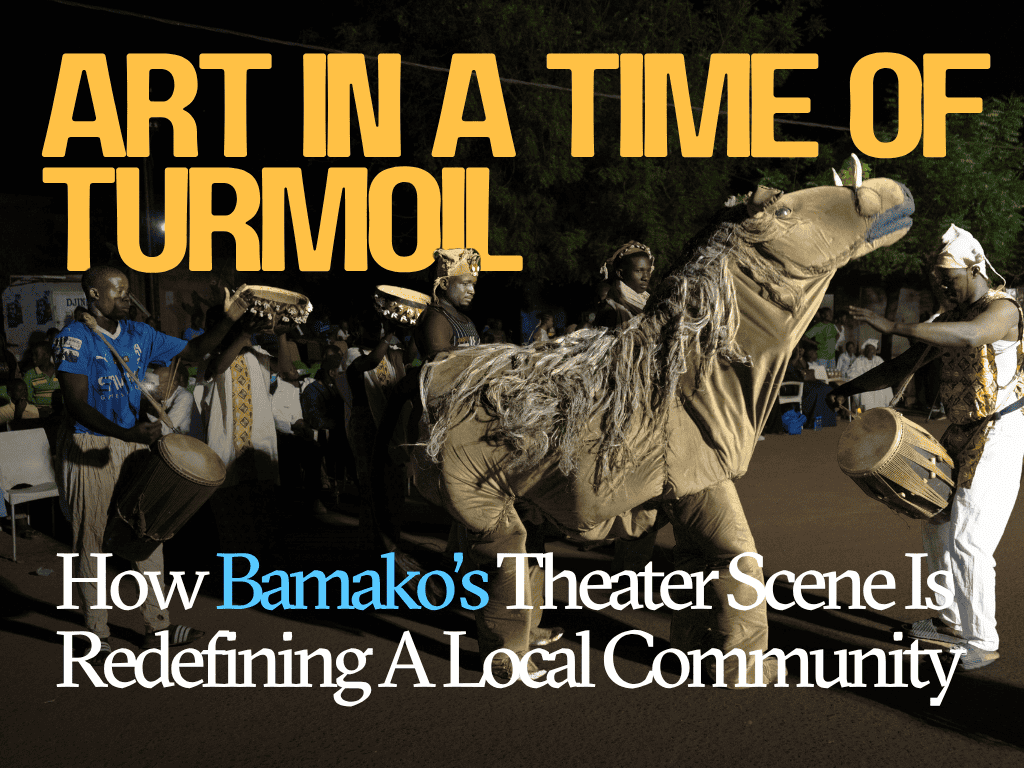

I arrived early in order to sit in the front row and have a good view of the stage. A magnificent puppet show featuring giant puppets representing animals from the bush was performed. Dancers and singers accompanied them with an intense rhythm of balafon and tam-tam.

After the usual greetings reserved for the guests, and thanking the traditional leadership of the neighbourhood and the notables, Lamine Diarra, the initiator, gave an overview of the context and objectives of the new project called Ventre des Praticables, or The Belly of the Platforms.

For him, this event was an opportunity for young people to speak about the issues that concern them, addressing the older generation and decision-makers without filters. I listened with deep emotion to the many testimonies shared by these young people, presented as audio recordings. For me, it represented a new vision of popular theatre, centred on real issues as the foundation for future projects.

Getting these young people to share their voices was a significant achievement. It was challenging enough to bring them together for an artistic project; getting them to open up was another hurdle. I understood their mindset—their hopes and shattered dreams. Many had built walls of silence about their uncertain futures, weighed down by life's challenges, including unemployment, drugs, and insecurity. Many are still torn between their passion and the pressure to conform to societal expectations.

Art, as perceived by many, is simply a distraction

Art, as perceived by many, is a mere pastime, a playful activity. To them, art is simply a distraction that interests only a certain segment of society and foreigners and is not a real tool for bringing about social change. Moreover, as some will tell you, "The priority when you're hungry in a country in crisis is not to have fun."

Seen from this angle, I could easily think that the mere presence of young people and notables at this popular evening event served as an affirmation that Kuma So had already won.

Making the community an integral part of the project was a wise choice. I now understood why Lamine Diarra had always emphasised transparency and credibility by involving the residents of the neighbourhood in every new project conception and organising public meetings to explain how he used project funds.

Even though the Les Praticables Theatre Festival has remained on its feet since 2017—unlike others that disappeared after just a few editions—it is not yet time for the organizers to celebrate victory.

Can we talk about censorship? It’s undeniable that artistic creations, artists, directors, authors, and composers often have to set up certain safeguards.

Words and gestures are carefully chosen. We continue to speak of justice, economic and social crises, resilience and suffering without ever naming anyone. Malian artists work within a difficult political context and we know that in many African countries, journalists and artists who speak truth to power are the first to be silenced.

Today, one of the major challenges for artists in a country in crisis like Mali is to awaken public consciousness, curate testimonies, and allow the population to question decision-makers without this being seen as an incitement to violence or an act of rebellion.

For Lamine Diarra, artists must continue to hold up a mirror to their leaders, allowing them to gain a more objective view of society. An event like Les Praticables can help them see the anomalies and injustices in society and provide a voice for the voiceless.

Change, after all, is incremental. Today, Lamine Diara tells us he is letting out a sigh of relief, as the Malian authorities seem to have finally heard the cry of Malian artists.

"For a long time, the Malian authorities and their partners did not pay attention to placing culture at the heart of their development projects. Now, with the new policy led by the transitional government in Mali, which has decided to make 2025 a year dedicated to culture to strengthen national identity and promote the country’s cultural diversity, I think there is finally a glimmer of hope!"

Perhaps this glimmer of hope will withstand the impact of the crisis and meet the expectations of Malian artists. Who knows? As our English friends say, "We can only wait and see."

Lisez la version originale en français ici.

This article is created in partnership with the DOEN Foundation. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of the DOEN Foundation.