Article created in partnership with the DOEN Foundation.

Far from the bustle of downtown Bamako, tucked away in a quiet neighbourhood, lies the headquarters of the Anw Jigi Art association. At its helm Assitan Tangara, embodies a new generation of socially engaged artists - deeply rooted in their communities and guided since childhood by a passion for the stage.

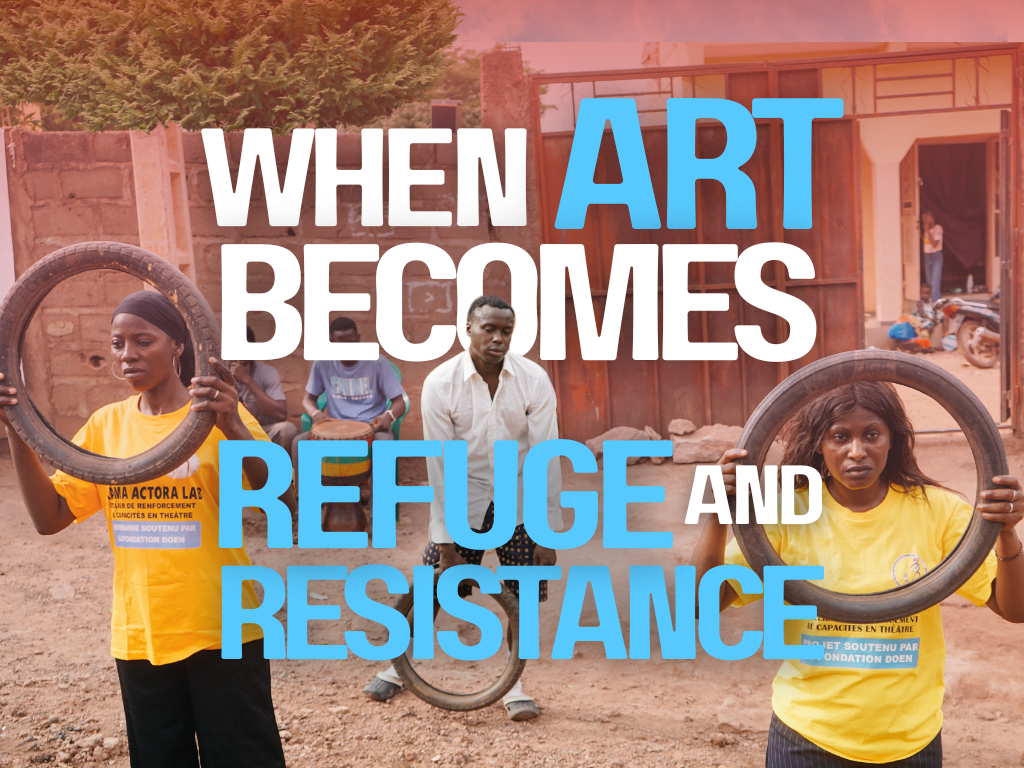

To reach the headquarters of Anw Jigi Art in Djalakorodji, a northern suburb on the outskirts of Bamako, I had to navigate chaotic, uneven roads. However, with the generous help of local residents, I finally found my way. Brightly coloured posters and recycled tires marked the entrance, signalling I was about to step into a truly artistic world. It was in a modestly built house, recently transformed into a cultural centre, that I met Assitan Tangara - an actress and storyteller of understated elegance and founder of the association. Assitan has also recently become president of the Funu Funu Federation (see below), a collaboration between Anw Jigi Art and other creative groups in the country.

Her appearance set her apart from the artists I was used to meeting. Dressed in a simple boubou, Assitan looked like an ordinary woman, far removed from the Malian artists I usually encountered, who often stood out with strikingly original styles - layered in handcrafted jewellery and rich local textiles.

Referring to her audience of everyday Malian women, Assitan confided with a smile, “you have to look like them to earn their trust”. It was a sincere, grounded, introduction, perfectly reflecting the spirit of her commitment to community work.

Resilience is my compass

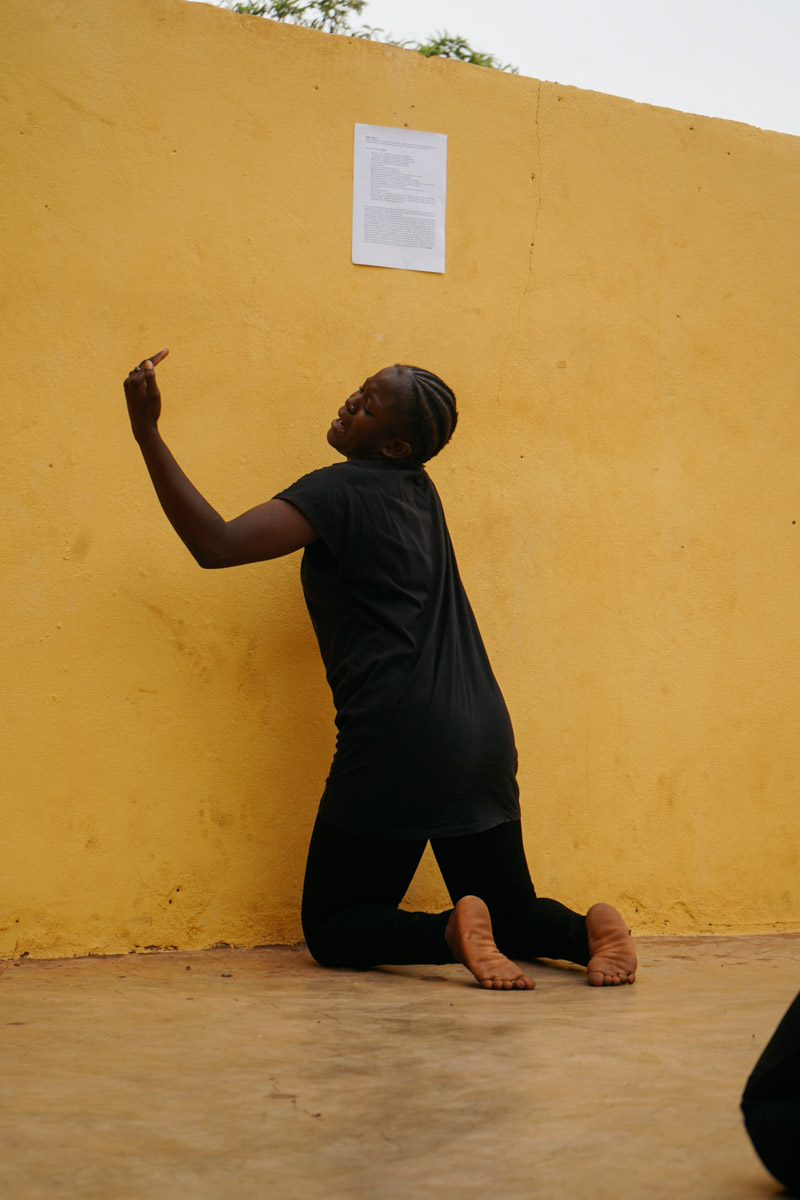

Assitan uses theatre as a tool to raise awareness, educate and amplify the voices of the forgotten. She has truly made the stage her theatre of struggle. From the very beginning, Assitan understood that choosing an artistic path meant facing public scrutiny and overcoming countless hurdles. Today, that hard-earned resilience guides her like a compass: “I always take trials as lessons. You have to hold onto your beliefs, you need to have a goal.”

Assitan places her faith in art, seeing it as a true instrument of dialogue, a bridge that can connect social groups and generations. “For dialogue to happen, people must be willing to meet, to speak their truths. And Mali today is in dire need of that.”

Her eyes welled with emotion as she spoke about her play Sinankouya—about the tradition of jestering kinship that binds even divided ethnic groups, using laughter and dialogue as tools for deeper understanding.

“We listen to their stories. From their voices, we begin to write.”

Since its founding, Anw Jigi Art has been devoted to creating a space where women can speak freely, claim their rightful place and spark social transformation. During discussion groups with the women in the community, the topics addressed touch on many taboos in Mali: menopause, menstruation, divorce, or gender-based violence are all talked about. Without imposing judgment or their own viewpoints, the writers and performers listen carefully, collecting slices of life to be later transformed into theatrical works.

An example is the Moussoya Gundo project, where Assitan and her performers challenge religious injunctions and socio-economic barriers. The title translates to “secrets of women” and the play has created a space for dialogue with women from diverse backgrounds. Above all the project sheds light on the religious and social constraints that force women into subservience.

Assitan wants her theatre to be profoundly social, rooted in reality and inspired by the lived experiences of the most vulnerable. “We go to them, we listen to their stories. From their voices, we begin to write.”

The stages for her plays are not confined to traditional theatres. The performances come alive in the streets, in markets, in courtyards, and even aboard sotramas—the crowded minibuses of Bamako. Her decision to perform outside of conventional venues carries deep meaning. She chooses to speak in spaces where people struggle, where life itself unfolds. And this means that over time, the work of Anw Jigi Art has grown into a form of cultural activism.

This breaking of silence can sometimes stir tensions within households. Through plays addressing domestic violence, some women now dare to speak out and denounce what they endure. Not all men welcome this shift as it means that they would have to shake up long-established norms dictated to them and their families by the Muslim faith and entrenched traditions. Despite these obsatcles, Assitan and her team keep the pressure up. For Anw Jigi Art does not just want to speak about society, it wants to transform it.

Unfortunately, not every subject can easily be tackled in public spaces. The young artist recalls a chilling moment in a sotrama - one of Bamako’s shared minibuses used for public transport - when she brought up the issue of rape.

“As soon as we introduced the topic, it was as if there wasn’t a single person in the minibus, even though it was packed. Before that, we had discussed many other subjects and people were engaging, co-operating. But the day we brought up rape, no one dared to speak.”

Assitan shared with me that Mali is going through a period of crisis, with many challenges to overcome. “As an artist, do you set limits for yourself when it comes to addressing certain topics, especially those considered sensitive? Not at all! There’s always a way to approach things, you need to choose the right place to do it, that’s all. That day we decided to change our strategy.”

To break the silence surrounding the taboo of rape, Assitan turned instead to an alternative, favoured listening circle: the tontines. These women’s groups exist in almost every neighbourhood, workplace, family or market. A form of collective savings scheme, tontines allow women to support one another financially. But they also offer a space where women can speak freely about their daily lives.

Assitan’s new strategy was picked up by a partner radio station, curious to know why this taboo topic was being discussed in the tontines. This in turn helped amplify the project’s reach and bring the issue of rape into discussion beyond the circles of tontines and sotramas.

Assitan does not claim the label of activist, yet her work as a campaigner for women's rights speaks volumes. By setting up her base in a neighbourhood deprived of cultural offerings, she lays bare the struggles she fights for and the commitments she upholds. Through her, Anw Jigi Art has become both a space of expression for young people and a refuge for women. Her plays, performed in the local Bambara language, strike directly at the heart of the community, allowing forgotten voices to be heard, and unseen wounds to be healed.

Bringing change to women’s lives

The transformative power born from these theatrical moments goes far beyond the stage. It directly impacts women’s lives, offering them not only a voice, but also a new foundation on which to stand and build upon.

On the outskirts of Bamako, I meet a young woman carefully inspecting her cakes, baked earlier that morning for the day’s orders. She moves with ease, as if she had been doing this all her life. A determined woman in her thirties, Aminata Tangara has been involved in Anw Jigi Art since its inception in 2012. Alongside theatre, Anw Jigi Art offers financing for young women to learn a new trade. Aminata didn’t hesitate and is among those who seized the chance to take their future into their own hands. Her dream has always been to master pastry-making. With Anw Jigi Art at her side, the only requirement to learn these skills was an ID card. Everything else was provided for by the organisation.

Today, with her diploma in hand, Aminata has become her own boss. She started a small catering business and hired five other young women who, in turn, now support their families. “Before, I couldn’t provide for myself. Now, I am independent,” she says proudly. Aminata also began growing chili peppers on her own small plot of land and processing local products to sell.

The support Aminata received went far beyond financial independence. The young woman has been completely transformed. Immersed in a world of artists, attending theatrical performances and engaging in conversations about the country’s social realities, her outlook on family, education and the role of women has been profoundly reshaped. “Before, when I scolded my children, I would shout at them— something I no longer do. Now I take the time to talk with them and listen.”

Aminata also tells me how certain theatre plays opened her eyes, helping her realize that there should be no distinction between boys and girls. “It used to be my daughter who did all the housework while her brothers played. Now, everyone shares the chores — even if some neighbours criticize the way I do things.”

A mother, an entrepreneur, a pastry chef and farmer, Aminata embodies a new generation of women in Bamako who are breaking away from tradition and refusing to be confined to the role of housewife alone: “One man on his own cannot support a household. Every woman must contribute her share,” she says.

Not far away, in a quiet house, another woman pedals steadily on her sewing machine. The Tabaski feast is drawing near and many pending orders need to be delivered. The life of Fatoumata - affectionately called Fanta in the neighbourhood - had also been transformed.

This young mother of three had been bored, her days monotonous, longing for an activity that could bring her an income. Then one day, Assitan Tangara’s sister made an introduction that ended up changing Fatoumata’s life forever. Today, she is in her third year of training in tailoring and is managing to make ends meet.

Fatoumata radiates a quiet strength. She clothes her family, earns a bit of money, and contributes to the household expenses. “I no longer depend on my husband for the small needs of daily life - he is very proud of me,” she says with a shy smile.

“I always believed my role was limited to taking care of the house and raising the children. Now I know I can do more,” She tells us of her pride in practicing a trade that gives her recognition in society and, above all, sparks her children’s curiosity. “When they see me working on my sewing machine, they come closer and want to do the same as Mama. I’m happy that my daughter also wants to learn how to sew. It reassures me to know that she already understands she can have a profession and not just be a housewife doing only what is expected of her.”

Giving children the courage to break the silence

The association does not focus solely on women, it also places a strong emphasis on children. From the earliest age, the little ones are introduced to art through storytelling, theatre, writing, and stage design.

Assitan Tangara told me about a powerful moment during a workshop when a 10-year-old boy, overcoming his shyness, improvised a scene about the quarrels in his family. “Why do parents always shout at us instead of explaining things?” he asked in front of the others.

That day, his courage broke the silence - much like the time when a girl of the same age sent Assitan a text about her mother, a doughnut seller. “My mother is a queen to me, she is as brave as a lioness,” she wrote, her words brimming with pride.

In this once-neglected neighbourhood, the practice of theatre has been profoundly transformed. The new energy brought in by the association has turned theatre from a marginal activity into a space of expression and pride. Thanks to the power of social media and the encouragement of elders, young people now dare to proclaim clearly: “I am an artist.”

It is a true victory, proof that art, in the hands of women and children, can become a powerful tool for dialogue, solidarity, cohesion, and transformation.

“I am a director who speaks the necessary truths.”

Back in Djalakorodji it’s celebration day. Women, young people, cultural institution representatives, artists, and journalists all come together at the headquarters of Anw Jigi Art, drawing the curious gaze of children perched carefully on tin rooftops, captivated by the magic of theatre.

Three performances are staged as part of the closing ceremony of the Doni Blon program, also known as the Great Vestibule of Knowledge. The day marks the culmination of several months of training of young talent from underprivileged neighbourhoods and art schools, united by a single goal: to retell the story of Mali in a new way. Born from the need to nurture a new generation of Malian actor-authors, the program draws on the expertise of several trainers from Mali and elsewhere in West Africa.

It was within this framework that Moussa, a young director, really stood out to me. With a calm demeanour, a measured tone, yet words that cut deep, he presented two plays to the audience: one on the ravages of drugs among young people, the other on the unseen wounds of divorce.

“When two adults divorce, they think only of themselves. But the children — they are the ones who suffer.” It is precisely for these children that Moussa took up the pen. To find inspiration, he seeks out the young where they are, in the streets. “We immerse ourselves in the neighbourhoods. We observe. On social media, you see young people wandering aimlessly, as if cut off from the world… Some think it’s cool. But what does it really bring them?”

For Moussa, the stage is the world that surrounds him. His work is not concerned with fiction. For him, theatre is not mere entertainment. It is an artistic space meant to raise awareness and spark self-reflection. “Theatre forces you to ask questions of yourself. Am I on the right path? What do I need to change?”

Like many other artists at Anw Jigi Art, Moussa chooses to voice his thoughts directly where people live. His theatre is one of proximity, rooted in daily life. For him, any subject can be addressed and no subject is off limits, provided it is spoken about with honesty and without evasion. “If we start being afraid to tackle certain issues, then we’ve already failed. Our mission will have lost its meaning.”

The struggle Moussa carries is not only cultural but social and political as well. However, just like Assitan, he too rejects the label of activist. “I am a director who speaks the necessary truths, in the places where they must be spoken.”

Assitan Tangara transforms disadvantaged neighbourhoods into a source of inspiration by collaborating with artists like Moussa. The work they produce reflects social reality and creates a space of expression for the invisible - those whose voices are rarely heard. When seen as a whole, Anw Jigi Art’s performances do more than provide a valuable source of hope for young people. They turn art into tools for dialogue, for liberty and above all, for women’s emancipation.

The Funu Funu Federation

Anw Jigi Art and other players in the Malian arts world joined forces to create the Funu Funu Federation in order to make their actions more visible and sustainable over time. Funu Funu, which means “whirlwinds” in the Bambara language, brings together artists from four different disciplines: puppetry, dance, photography and performance. By uniting their efforts into collective actions, the foundation hopes to have a greater impact on the community.

However, I question the sustainability of a foundation that brings together artists working in such different spheres. And, what is the future of community empowerment initiatives in a world where democratic processes are continually being undermined? Such a foundation would surely face the crucial issues of funding, and more importantly, governance. Stable resources might be lacking and rivalries could frequently arise over the pursuit of grants, undoubtedly weakening collective efforts. More crucial questions came to mind:

A federation's vitality hinges on its foundational structure; if it isn't solid enough to ensure equitable representation for all disciplines, it risks alienating members. This structural weakness is often compounded by a lack of essential support, like mentorship and training, which can lead to discouragement and professional failure for individual artists. Ultimately, these issues- from logistical shortcomings to poor professional development - could weigh heavily on the organization's strength, preventing groups like Funu Funu from reaching their full potential.

Surely the “whirlwinds” will just blow themselves out? But Assitan dismissed these concerns with confidence. “I can say today that Anw Jigi Art has gained in visibility and reputation through Funu Funu, and it’s the same for the others. The people we united with have serious organizations and are strong in their respective fields. Today, Funu Funu is one of the most talked-about federations in Mali, thanks to the initiatives it has successfully led over the past years.”

Women like Aminata and Fatoumata whose lives have been touched by Anw Jigi Art, would surely agree.

Author’s note by Aminata Fadiala Konate.

Lisez la version originale en français ici.

This article is created in partnership with the DOEN Foundation. The views expressed in the article do not necessarily reflect those of the DOEN Foundation.