Manono’s lithium millionaires

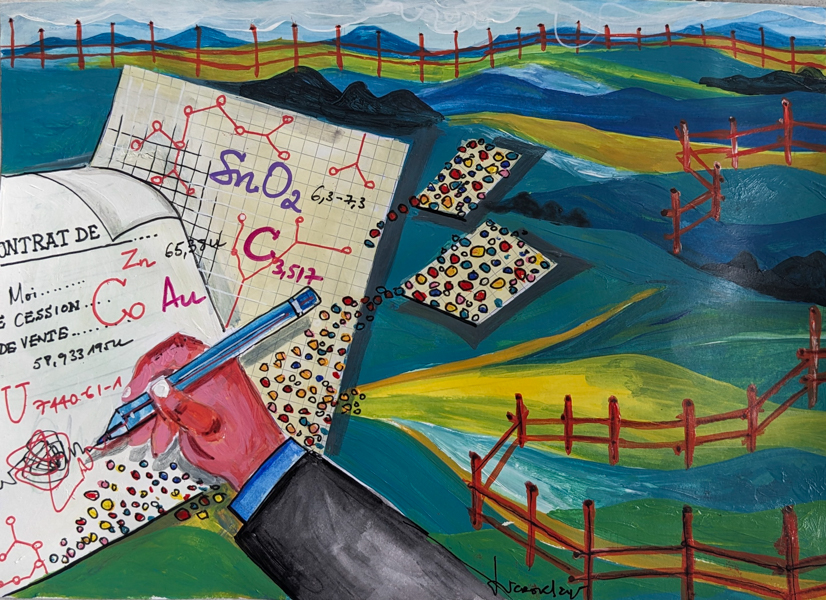

While numerous reports expose how multinationals have acquired natural resources cheaply, polluted communities, and exploited workers, the role of influential African political elites in facilitating these practices has received far less scrutiny. The DRC chapter of ZAM’s new transnational investigation into Africa’s Sell-Outs documents a partnership between politically connected Congolese actors and a group of foreign businessmen, to the detriment of a mining community.

The small town of Manono in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) sits at the centre of a geopolitical scramble for minerals essential to green and military technologies. Chinese and American companies are competing for access to what is believed to be one of the world’s largest lithium deposits. Yet the arrival of the world’s superpowers marks only the latest chapter in a long wave of commercial activity that has generated millions of dollars in deals between politically connected Congolese and a small group of foreign businessmen, leaving the people of Manono with little to show for the wealth beneath their feet.

Strategic resources

On June 27th, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo signed a U.S.-brokered peace agreement, prompting cautious international optimism for an end to the ongoing conflict in Congolese territory, which has claimed millions of lives and displaced countless others. Mirroring the recent U.S.–Ukraine minerals deal, the agreement closely ties access to strategic resources to what is being presented as “political stabilisation.” Under its terms, both nations have made tentative commitments to halt hostilities, withdraw troops, and end support for armed groups operating in eastern Congo.

Tech titans are moving in

As part of the deal, Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi has once again offered the DRC’s vast mineral wealth to foreign interests—this time to American companies—in an effort to secure U.S. support for peace initiatives. The agreement explicitly states that Rwanda and the DRC will "de-risk mineral supply chains and formalise mineral value chains linking both countries, in partnership, as appropriate, with the U.S. government and U.S. investors.” How this will be achieved, what “de-risking” actually entails, and who stands to benefit remain unclear. “We’re getting, for the United States, a lot of the mineral rights from the Congo as part of it,” said President Trump ahead of the signing ceremony.The deal has drawn renewed attention to Congo’s largest untapped lithium deposit, situated in Manono territory near Manono town in Tanganyika Province, DRC. For nearly a decade, the mine has been the focus of intense competition among Chinese, Australian, and Congolese business interests, all seeking to develop one of the world’s richest lithium reserves.

Frustrated community

In the wake of the peace agreement, US-based mining startup KoBold Metals—backed by tech luminaries Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates—together with global mining giant Rio Tinto, are now targeting Manono’s lithium. In a contentious move, KoBold signed an agreement with the Democratic Republic of Congo that positions the US firm to acquire the disputed Manono lithium deposit. However, a tangle of lawsuits and allegations of corruption clouds the mine, as companies including Chinese mining giant Zijin assert competing claims to the same deposit. Meanwhile, the local community, eager for mineral wealth to translate into much-needed development, is growing increasingly frustrated.

Green energy hopes have yet to deliver

Manono is a small town, surrounded by rice fields and manioc plantations, its skyline broken by the giant skeletons of Belgian colonial-era mining infrastructure. Its narrow roads are cropped by Euphorbia hedges, creating something like a botanical garden maze that curves around schools, churches, and shops, and is alive with families, traders, and craftspeople. Larger red-earth roads are lined with magnificent mango trees, whose fruit is harvested at twilight in mango season by schoolchildren on their way to class. Sometimes, mangoes are the only food that will go in lunch boxes that day. The town lacks infrastructure, water, and electricity. Unemployment is rife, and many people have long since taken up artisanal mining, mining by hand with shovels and buckets, to make ends meet.

Manono’s former colonial mine remains within living memory, and many residents recall that period as one of relative stability, perhaps reflecting the challenges the town faces today. In recent years, the massive lithium discovery thrust Manono into the green energy spotlight, raising hopes as mineral exploration companies returned.

Muddled and inept

Residents then waited for industrial mining to begin, only to watch lithium prices surge and crash again. As a procession of companies came and went, each trying to stake its claim to the deposit, the Congolese government failed to capitalise on the price boom or secure a stable partner, managing the project in a way that seems at best muddled and at worst deeply inept, entertaining a complex mass of speculation, business deals, and itinerant dealmakers rotating between companies, inking lucrative contracts and reaping profits.

Within 50 kilometres of Manono, five companies connected to a network of international businessmen now hold exploration and mining permits spanning more than 1,220 square kilometres—an area larger than Hong Kong.

These businessmen have earned millions of US dollars over the past 15 years through share-based payments, share sales, and consultancy fees tied to deals involving Manono. Yet, despite the substantial sums exchanged and investor forums promoting a “new lithium Eldorado” in Manono, none of these companies have conducted any mining or brought lithium to market.

“A small group of people enrich themselves to the detriment of our country”

Civil society groups have criticised how key deals in this carousel have unfolded. Jean Claude Mputu from the NGO Resource Matters told ZAM that, “Bad governance of the [lithium] sector, a lack of transparency, opaque conditions of license distribution and the complicity of the political class between all sorts of intermediaries, allows a small group of people to enrich themselves at the detriment of our country.”

Congolese counterparts

Central to Manono’s lithium deals is a group of international businessmen collaborating with politically connected Congolese counterparts. Prominently featured on the Congolese side is Guy Loando, a lawyer who has served as Minister of State in charge of Regional Planning since April 2021 and recently transferred to the post of Minister of Relations with Parliament. (He also leads an anti-poverty organisation called Fondation Widal.) Alongside Loando is Jean-Felix Mupande, the former head of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Mining Cadastre (CAMI). CAMI, which operates under the Ministry of Mines, is responsible for overseeing mining titles and managing access to the DRC’s vast mineral resources.

CAMI is designed to serve the interests of investors, the state, and the Congolese people, evaluating applicants for financial robustness, technical capacity, and compliance with environmental and social standards. The agency also manages the approval and registration of all mining and exploration rights, which are then submitted to the Ministry of Mines for permit issuance. Under Jean-Felix Mupande, CAMI has overseen more than a decade of lithium deals in Manono, playing a key gatekeeping role for companies seeking to exploit the town’s mineral wealth.. While CAMI’s recommendations typically guide the ministry’s decisions, Mupande insisted that CAMI “does not grant mining rights” and that “this authority lies with the Minister of Mines.”

A German mining veteran, a Chinese ‘godfather’ and regime links

On the international front, these Congolese VIPs engage with Klaus Eckhof, a German mining veteran and serial mineral prospector, and Cong Maohuai, a Chinese businessman reportedly close to the former Kabila regime, whom the media have dubbed the “godfather” of Chinese mining deals in Congo. Loando and Eckhof’s professional relationship dates back to at least 2011, when the Congolese lawyer witnessed a deal between Eckhof’s Ferro Swiss AG and the state-owned company SOKIMO. By 2014, US regulatory filings list Loando as a shareholder in another company, Panex Resources Inc., then led by Maohuai, Eckhof, and their partner Mark Gasson.

Handsome profits

Guy Loando, Klaus Eckhof, and Cong Maohuai are well-known in the DR Congo’s mining sector and have started dozens of mineral exploration companies. Analysts say that Klaus Eckhof and Cong Maohuai have made a name for themselves over the years by identifying world-class Congolese mining assets before others. “Unfortunately for investors, however, none of the Manono lithium projects are making any money, though Eckhof, and no doubt Maohuai too, have profited handsomely,” commented Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, a research consultancy specialising in DRC’s political economy.

In correspondence with ZAM, CAMI head Jean-Felix Mupande confirmed that in 2012 his registry processed two crescent-shaped exploration concessions on the outskirts of Manono for Alphamin Resources Corp. Shortly thereafter, Klaus Eckhof joined Alphamin, serving for only a few months. Following his departure, the company wrote off the Manono concessions as “worthless.”

What follows is a glimpse into the deals, networks, and substantial profits that have shaped the business activities of mineral exploration companies in Manono.

The “only ones who perform”

It was after Alphamin that AVZ Minerals, founded and led by Klaus Eckhof and one of the first companies to explore lithium in Manono, entered the scene. Public records indicate that, in that year, AVZ acquired Alphamin’s Manono concessions from Medidoc FZE, a company owned by Eckhof’s long-time associate, Dr Andreas Reitmeier. There is no public record detailing how Alphamin’s concessions came into Medidoc FZE’s possession, which would normally have required CAMI approval for any such transfer.

When asked to explain the deal, Reitmeier told ZAM that Alphamin had written off the concessions as “worthless,” and they were therefore acquired by Medidoc without compensating Alphamin. CAMI head Mupande contradicted this account, telling ZAM that Alphamin had simply “become AVZ” through a name change. Eckhoff offered a different explanation, telling ZAM: “We offered to pay the fees and agreed that Alphamin transfers us the licenses. Nobody else was interested in those grassroots licenses. We are not the most favoured, but we are the only ones who perform, find deposits, and can raise money in international markets. There is no preference for us other than that he [Jean-Felix Mupande] knows we can actually deliver and progress projects.”

Whatever the case, public reporting shows that AVZ paid Medidoc FZE US$200,000 and 30 million ordinary shares to acquire the very same concessions Alphamin had written off just a few years earlier.

In the following months, a third concession, located at the centre of AVZ’s Medidoc acquisition, was revoked and reassigned under contested circumstances to a new joint venture, Dathcom Mining SA, formed between Cong Maohuai’s company, Dathomir Mining Resources, and the state-owned enterprise Cominière. AVZ subsequently joined Dathcom, paying Maohuai’s Dathomir US$750,000 and granting it a 12.71% stake in AVZ. According to a Boatman Capital report, Dathomir was 20% owned by Guy Loando and his family.

As part of the agreement, Loando subsequently joined AVZ’s board as a nominee of Dathomir. AVZ would later pay Loando and Maohuai’s Dathomir a combined total of more than US$6 million, along with shares valued at nearly US$5 million, while Loando received at least US$800,000 in shares.

The deals secured rights to one of the world’s largest untapped lithium deposits

Amidst all these transactions, as complex and confusing to outsiders as they are profitable to those organising them, it is clear that the deals secured Eckhof, Loando, and Cong’s positions on the boards of companies holding rights to one of the world’s largest untapped lithium deposits.

Dramatic delisting

AVZ was merely the opening act in the businessmen’s Manono saga. Eckhof and Loando departed AVZ in 2016 and 2019, respectively, after which the company’s fortunes began to unravel. A two-year trading halt, a series of legal battles, and the revocation of its central concession by the Ministry of Mines did not result in a single tonne of lithium leaving the ground. This was followed by a dramatic delisting from the Australian Stock Exchange in May 2024, which trapped thousands of investors and erased billions of USD in valuation. (AVZ, however, has not yet conceded. It continues to pursue numerous court cases at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes and the International Chamber of Commerce to reclaim rights to the Manono concession.)

“AVZ had originally given the community hope for a better future, including development and jobs,” says Abbé Moise Kiluba, Manono’s Catholic priest and head of the town's civil society. “The population of Manono would like, through the exploitation of lithium, to see the transformation of socio-economic life towards modernity and to obtain employment, preferably with more than crumbs for wages.”

We meet Kiluba in late 2024, in his modest office at the heart of Manono, where a queue of people waits patiently outside, seeking guidance on a range of social and legal issues affecting the community. Nearby, motorbikes and heavy lorries roar through a junction leading to the town’s outskirts. Towering over the centre of town is a billboard promoting President Tshisekedi’s Local Development Program for DR Congo’s 145 territories.

Another company hosted the second act

Just a few kilometres away from Abbé Moïse Kiluba’s office, past the town’s red brick cathedral, sits the local headquarters of Tantalex Resources, which hosted the return of Eckhof and his group in the second act.

In July 2021, six months before Klaus Eckhof officially joined the company, Tantalex reached an agreement with Minor SARL, owned by Maohuai, committing US$4.5 million and 55 million shares to the Congolese company, while securing for Tantalex a stake in an exploration licence for a concession directly adjacent to AVZ’s.

All in the family

Around the same time, Rome Resources—a company directed by Mark Gasson, in which Eckhof held an 18 per cent stake—acquired Medidoc RD Congo, another firm led by Gasson and owned by Reitmeier. The company’s name closely resembled that of Reitmeier’s Medicoc FZE, which had played a central role in the original Manono transactions involving Alphamin, Medidoc FZE, and AVZ. The acquisition granted Rome Resources a stake in an exploration permit located several hundred kilometres north of Manono, where the majority shareholder was Investissement et de Développement Immobilier (IDI), a company owned by members of Jean-Félix Mupande’s family, the head of CAMI.

Back in Manono, in the months following the transactions involving Medidoc Congo and IDI, Tantalex secured a new mining permit. While already developing his next venture in Manono, Eckhof departed from Tantalex and, about a year later, retained more than US$251,000 in Restricted Stock Units and stock options.

Simultaneously, CAMI was reviewing a bid from another Eckhof-affiliated company, AJN Resources, for a portion of AVZ’s original, now revoked, concession. Documents indicate that Loando, who is now a government official, was listed on the proposed oversight committee for the deal. If successful, Eckhof stood to receive a 10% finder’s fee on a license he had already “found” twice before, first for Alphamin and then for AVZ. In a press release at the time, Eckhof expressed confidence that the acquisition was imminent, describing it as “a key driver in alleviating poverty and improving social conditions” through local infrastructure development and job creation.

Future Mining belongs to the wife of Minister Loando

However, despite Eckhof’s optimism and the aligned business interests with the family of CAMI chief Mupande, the deal did not materialise. A second AJN bid for Manono area permits, through Cong Maohuai’s Mbanga Mining SARL, also failed, but a third bid was ultimately successful. AJN paid US$100,000 to Future Mining Company SARL for a stake in a concession located less than two kilometres from Chinese Manono Lithium’s. Future Mining is owned by the wife of Minister Loando.

Shift to China

Things then began to shift in Manono. In August 2023, Jean-Félix Mupande departed from CAMI and was replaced by Paul Mabolia, the former head of the Kimberley Process in the DRC, an initiative designed to ensure the diamond trade remains free from “blood diamonds.” Since, Chinese mining giant Zijin and its joint venture, Manono Lithium, have been granted rights at Manono which are contested by AVZ.

Eckhof, Maohuai, and Loando appear to have taken a back seat since Manono Lithium entered the scene. However, their actions through prior permit transfers, substantial payments, and share exchanges, along with the involvement of family members of mining regulators and parliamentarians in joint ventures, which are legal under Congolese law but questionable in practice, have contributed to generating up to US$28 million for Cong and Loando’s Dathomir alone, benefiting “mysterious shell companies controlled by controversial deal makers,” according to a 2024 Global Witness report.

“Companies come and go”

Meanwhile, despite AVZ being valued at billions of US dollars in 2022, its joint venture Dathcom paid less than US$260,000 in taxes across 2021 and 2022, according to the EITI. To put this in perspective, that tax contribution is roughly equivalent to the value of stock and options Klaus Eckhof received in a single year from Tantalex, only about four per cent of what Loando’s wife’s company, Future Mining Company SARL, received from AJN, and just 2.2 per cent of what AVZ itself paid to join Maohuai’s Dathcom joint venture.

Tantalex, Gasson, Loando, and Maohuai did not respond to ZAM’s request for comment. Mupande, however, told ZAM that “there was no law in Congo against family members of state agents holding mining concessions” and did not deny that his family held such concessions. Reitmeier stated that he did not know who owned IDI at the time the exploration permit was established and that he has never had any form of communication with Mupande.

“There is no law in Congo against family members holding concessions”

Eckhof told ZAM that AJN had stopped pursuing the project with Future Mining and that he does not personally own any mining or exploration licences, working only for public companies. “It’s normal that companies come and go… One of the problems is that Europe is not part of the exploration game, as the capital to fund a dream or hope is not there. Due to this lack of funding, there is limited comprehension,” Eckhof concluded.

Criticising the schemes that have seen millions of dollars flowing between companies and businessmen but left the mining area with little benefit, a member of the civil society coalition Tous Pour la RDC, who spoke anonymously for security reasons, said the mining sector in Manono reflects a deeper political culture of self-enrichment. “It all stems from a selfish desire to enrich oneself – a desire that can be seen at the same time in the political sphere, among traders working for multinationals, and among managers of companies in the state portfolio, especially mining companies,” the coalition member explained.

Companies and investors still "live as enemies of the community”

It is unclear if the arrival of KoBold and the ‘minerals-for-security-deal’ with the US represents the end of Manono’s speculative frenzy. With the government’s opaque policy, the pending lawsuits and multiple companies claiming rights to the town’s lithium deposit, it all feels more like the next chapter than the end of an era.

Chinese miner Manono Lithium is making its presence felt: new roads and electricity to power the mine are on the horizon, and workers from China and across the DRC are arriving daily. Yet, its role as a community partner looks far less promising. On August 20, 2025, the Initiative for Good Governance and Human Rights reported a conflict involving KAMOA COOPER S.A., another subsidiary of Zijin, Manono Lithium’s parent company, near the mining hub of Kolwezi. The findings echo problems already surfacing in Manono: violations of the mining code, lack of dialogue and transparency, and reliance on political influence. In Kolwezi, local communities accuse the company of river depletion, toxic waste pollution, land seizures, forced evictions, and the arbitrary arrest of 72 peaceful protesters demanding fair compensation and resettlement.

In Manono itself, tensions are escalating. The company has begun expelling artisanal miners from its concessions, and nearby communities face an uncertain future. Villages such as Majondo, Matala, and Lwamba now risk displacement as preliminary mining activities steadily expand toward their lands.

Abbé Moïse Kiluba, reflecting on the decade since AVZ first arrived and the years since Manono Lithium SA took over, reminisces: “Up to now, it's been nothing more than research and the sale of mining perimeters, with millions of dollars evaporating between the individuals. Neither the public treasury nor the local community have benefited from this.” He calls on the DRC’s government to become “realistic and concrete.” “They must move away from empty rhetoric and, above all, be closer to the people and more sensitive to their cries of alarm... because companies and investors live as enemies of the community.”

This article was produced by the research collective The Rock Pool, with support from Journalismfund Europe.

See the instalments in this Transnational Investigation here

Sell Outs | The patrons who make the deals about their countries

Zambia | A corrupt political class

Zimbabwe | All the president’s minerals

Mozambique | Government Captured by Lobbyists

The Gambia | Fighting the businessmen who erode the wetlands

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.