Skin syndicates harm rural families and pay politicians — but good civil servants are fighting back

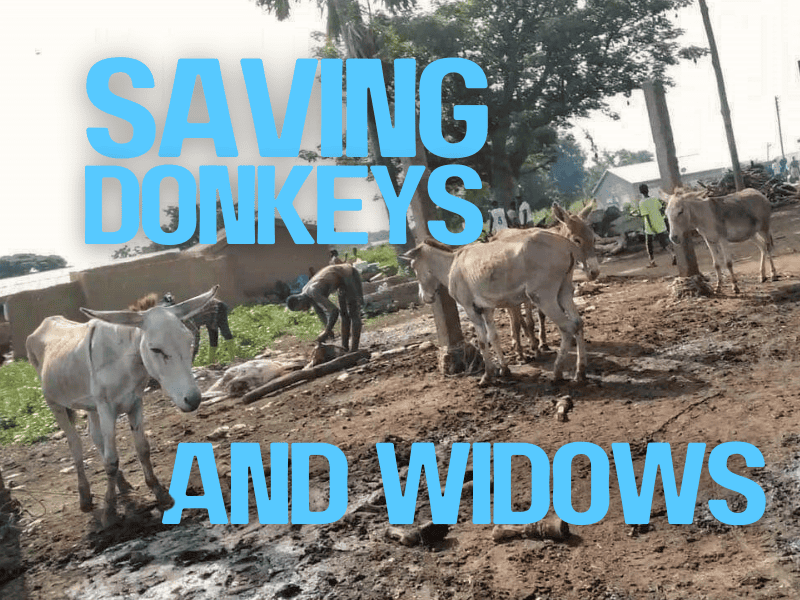

Rural families in northeastern Ghana and parts of the Sahel have been losing vital farm donkeys—essential for ploughing and transporting crops—to a syndicate that kills the animals for their skins. The primary victims are peasants, often single women and widows, who manage small farms to support their families. Together with civil society organisations, committed state officials have made progress in curbing the plunder, but their main obstacle now is political. “We can’t anger the traders who fund political campaigns,” a source within a political party said.

In Bolgatanga, near the northern border with Burkina Faso, communities have experienced what widow Sister Muniratu Ousman describes as “acute pain” after losing her only donkey to thieves. “I had tied it outside to feed, but when I returned, it was gone. I later found it lying lifeless, its skin removed. The government is doing nothing to stop it,” she says. Another widow, Hajia Suweiba, whose late husband left her a donkey to help on their farm, says her brother-in-law sold it to the syndicate despite her objections.

“Some community men sell the donkeys for money”

Under both formal and customary law, Ghanaian men are required to obtain permission from their wives and relatives before selling any common or family property. However, in many rural areas, these laws are often not enforced. “In our community, men have more authority, so decisions are made without consulting us,” says Suweiba. Fuseini Alhassan, a farmer from nearby Yorogo, confirms: “Many widows were left with donkeys by their late husbands to help them survive, but some community men sell them for money, leaving the widows struggling while the government does nothing to stop the trade.”

There is a formal ban on the donkey-for-skin trade in West African ECOWAS countries, but it still faces political stalling in Ghana.

Threatened resources

The trade in donkeys for meat has long existed in northern Ghana, particularly among the non-Muslim communities of the North and Upper East regions. Unlike their Muslim counterparts, who abstain from donkey meat for religious reasons, non-Muslims have traditionally slaughtered small numbers of donkeys for food, with their hides either burned or consumed along with the meat. In the past, because these numbers were limited, the practice attracted little concern, and theft was rare. The same pattern applied to other locally threatened species, such as pangolins and rosewood: pangolins were used for nutritional and medicinal purposes, while rosewood was harvested for furniture. But with foreign buying markets booming, all three are now being plundered.

Pangolins and rosewood

Sulemana Zakaria, a seasoned farmer in his late fifties from Yorogo, near Bolgatanga, has, over the past decades, watched more and more syndicates move in and exploit rural resources while authorities do nothing. Seated under the shade of a baobab tree, gesturing with hands calloused from decades of labour, he shakes his head when we mention donkey traders. “They come with money, always ready to buy,” he says, his voice laced with resentment. “First, it was just the donkeys. They’d take them in large numbers, skin them, and send the hides away. But then we started noticing the rosewood disappearing, too. Then hunters started complaining that their traps for pangolins were empty. It wasn’t a coincidence.”

Shipping containers

A few miles away, Kwame Amewu, a hunter in his thirties, shares a similar story while grilling grasscutter (a rodent) meat for sale by the roadside. “Pangolins were always around when I started hunting,” he says, his eyes fixed on the sizzling meat. “But now, you’re lucky to see one.” Pausing to weigh his words, he recounts how he recently followed a trail to Tema, a harbour warehousing area far south near the capital, Accra, which led him to a clearing filled with Chinese traders, Ghanaian middlemen, and sacks of unknown cargo. “I moved closer and saw what was inside—pangolins, some still alive, others dead, their scales being stripped off like peeling cassava.” Emotionally, he recalls how some traders mixed pangolins with donkey skins, while others cut rosewood logs, stuffing everything into shipping containers.

In Yorogo, Sulemana Zakaria sighs, rubbing his temple. “The government talks about banning rosewood logging, but it’s all the same traders. Smuggling donkey skins is driving the rosewood and pangolin trade. It’s all connected. If something isn’t done, soon there’ll be no donkeys, no forests, and no pangolins left.”

The rapidly expanding donkey trade is dominated by syndicates catering primarily to Chinese buyers. Veteran local trader Seree, whom we meet in his modest shop among mud-brick structures and rusted corrugated sheets in Bolgatanga, recalls clearly how the boom began. He explains that in 2013, a local officer from the Criminal Investigative Department (CID) in Walewale—the main town roughly 100 km to the south—introduced him to a Chinese couple, noting that donkey skins were highly prized in China for the production of belts, shoes, and bags. “The man even bought me a motorbike to help collect skins from local butchers,” Seree adds.

A white Chinese man

As flies hover over a pile of donkey skins drying in the sun and chickens peck near plastic buckets filled with murky water, Seree reminisces about the past before the arrival of the buyers. “We used to burn the donkey with its skin and remove the intestines first, just like we do with cows and goats. Then we would cut up the meat. At that time, we weren’t removing the skins like we do now,” he says, his dark, wrinkled face showing slight amusement. “Even that first white man (meaning Chinese) who came used to eat it. He would ask me to roast some for him.”

This marked the beginning of the large-scale donkey skin trade in the area. As word spread, more locals, particularly unemployed youth, became suppliers for the Chinese traders. The original couple left for China after about eight months, but other Chinese traders soon replaced them. Rising demand led to increased donkey theft, higher prices, and the expansion of the trade into neighbouring towns.

Dried skins carry the air of never-arrived development

Seree is still part of the network, but it doesn’t trouble his conscience. Sitting on a worn-out wooden bench next to his shop, in a maze of narrow, uneven paths that snake between scattered structures, he simply recalls events with a mix of nostalgia and resignation. Dried animal hides, mingling with the wafts of soldering wood from nearby food stalls, carry the air of never-arrived development.

Blue Coast Trading

By 2016, the donkey skin trade had become so lucrative that two Chinese men established a slaughterhouse—the Blue Coast Trading Abattoir—in Walewale, the hometown of then-Vice President Mahamudu Bawumia. This led locals to believe the narrative circulated by the donkey traders: that their operations were part of the government’s “One District, One Factory” initiative, a programme aimed at promoting industrialisation at the district level.

The abattoir was said to be a government factory

What lent added credibility to the story was that the abattoir’s owners swiftly secured approvals from the West Mamprusi District Assembly, the national Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drugs Authority (FDA), and the Veterinary Service—despite the fact that, in the same year, the West African regional body ECOWAS had imposed a ban on the donkey-for-skin trade, which was already impacting rural livelihoods. Technically, the permits were valid, as the wording referred only to “animals” and not specifically to donkeys. Yet no alarm was raised when the facility was found to include salting rooms for skins and residential houses for Chinese owners.

Our sources indicate that the local chief was aware, but “management told him that only old donkeys would be slaughtered” and that it would be “no more than 70 per day.” A local woman landowner, who had provided the site for the abattoir, became the supplier of the donkeys. In the end, the entire facility was enclosed with a high-security fence with wire mesh.

A high-security fence

The trade and slaughter at the abattoir expanded almost immediately. Local municipal assemblies issued movement and exit permits, facilitating the transport of donkeys in and the export of their skins. Many donkeys—some sick or already dead, as traders were solely interested in the skins—were smuggled into the abattoir from Burkina Faso and other neighbouring countries. And the scale was far beyond 70 donkeys per day. According to the regional Veterinary Service, by 2017, Blue Coast Trading was slaughtering between 150 and 200 donkeys daily, employing over 100 young men.

According to the same sources, the activity was also highly lucrative. Ghanaian suppliers were paid US$5.29 per kilogram, with buyers purchasing donkey hides averaging 7 kg for around US$37 each. We were told that the same hide could sell in China for US$1,160, yielding a gross profit of US$1,123 per hide. With exports averaging 14 hides per day, traders at Blue Coast reportedly earned over US$112,000 daily.

The Veterinary Service put its foot down

In 2018, the original owners packed up and left with their proceeds, but in 2019, they were replaced by another group of Chinese traders. These newcomers, too, obtained all the necessary permits—from the district assembly in Walewale, the FDA in Tamale, and the EPA, says Osama Sunder, the abattoir’s local management partner. This time, however, they encountered an obstacle: the Veterinary Service in the Walewale region was putting its foot down. “There was an ECOWAS ban on donkey slaughter; that was why,” Sunder recalls.

The ECOWAS ban had already been in place in 2016, but the difference three years later was that Walewale’s veterinary officer in charge, Alhassan Shehu, was intensifying efforts to halt the trade. Shehu and his colleagues had launched a tenacious campaign against the Blue Coast Abattoir and similar operations that had emerged alongside other branches of the syndicate in West Mamprusi.

An impossible mission

It seemed an impossible mission at first. The Blue Coast Abattoir circumvented the veterinary permit requirement by paying slaughter permit fees to the District Assembly instead of to Shehu’s Veterinary Service. The police assistance Shehu repeatedly requested was not forthcoming, as the District Police Commander refused to intervene, citing “directives from higher authorities.” The District Chief Executive claimed ignorance of the ban. And the Walewale District Assembly itself could not, it said in response to Shehu’s requests, close the abattoir “because it granted them the permit in the first place.” “They said it was now becoming a legal issue,” Shehu recalls.

Even Shehu’s approach to Northeast Regional Minister Yidani Zakaria, in which he asked that the minister consult Vice President Bawumia and explain that the syndicate was using Bawumia’s name, initially yielded no result. “The response I got was that (Bawumia) said he had never heard of this and simply asked that we deal with it,” Shehu recalls, resignedly adding, “There was really no push from the presidency to enforce the rules. So, while we were fighting, other government bodies were granting them permission to operate.”

COVID and awareness

COVID provided a temporary reprieve: in 2020, the slaughter at Blue Coast halted due to the lockdown, and the owners abandoned operations in Ghana. Simultaneously, awareness was growing that donkeys were a regional resource that should not be decimated. That same year, the Bolgatanga Municipal Assembly shut down the IT Sino Ghana Limited abattoir in Yikene. When, in 2021, another group attempted to restart the Blue Coast facility, they were met by Shehu and fellow district officials. The civil servants persuaded the Northeast Regional Minister and other authorities to inspect the abattoir; upon discovering both live donkeys and meat stored in the cold room, the delegation issued a stern warning: any further decline in donkey numbers would result in immediate closure. Subsequently, the owners sold off the operation and left.

When another new group tried to revive the slaughter in 2022, they were refused entry to the Blue Coast facility by the now cautious local manager, Osama Sunder, who advised them to seek official clearance or move north, where enforcement was still laxer. The group still attempted to smuggle skins into the dormant abattoir for processing, but Veterinary Officer Shehu and his team of new district officials intervened and stopped the plan. Further pressure came from Vice President Bawumia, who finally ordered the permanent shutdown of Blue Coast Trading. With the ban now actively enforced, the abattoir was at last put out of operation.

Meanwhile, a team of Agricultural Extension Service (1) officers had identified two additional unregistered slaughterhouses, one in Walewale and another 60 km east in Nalerigu, and closed them down as well.

Underground

Sadly, an overall happy ending to the donkey slaughter is still being delayed. The syndicate has gone underground, rotating private locations for the slaughter and using coded communications with high vigilance. When Tiger Eye managed to break into the network through an undercover reporter posing as a supplier, we met a local syndicate manager, Joseph, together with his Chinese boss—a young man with a stern, frowning face—at a compound near the abandoned Meat Factory in Zuarungu, close to Bolgatanga. The boss followed the conversation between the reporter and Joseph through a translation app on his phone, with the chat interspersed with nods and brief exchanges between Joseph and his boss.

A few subsequent exchanges allowed Tiger Eye to map a network surrounding four Chinese bosses operating in Bolgatanga, Kumbangre, Zuarungu, and Yikene, respectively. However, the operation effectively concealed the actual underground slaughter sites. On one occasion, an ‘agent’ provided an address, but upon arrival, the location—a securely walled compound containing a simple, dirty-brown-painted three-bedroom apartment—was abandoned. Another address located later likewise led to a vacant compound.

Ties with politicians stand in the way

Political will and robust law enforcement now appear to be the only means of protecting farming families, yet ties between the syndicate and certain politicians stand in the way. This was particularly evident in the region last year, during a period of intense campaigning ahead of the national elections held in December 2024. Mma Abiba Seidu, a widow in Bolgatanga—one of many who continue to fear donkey thieves—linked the government’s inaction to the electoral cycle. “They’re too focused on elections to help us. They allow this to continue, and I won’t vote for them.”

A governance expert within the (then ruling) NPP, speaking on condition of anonymity, confirmed this, telling us that a crackdown on the donkey syndicate could spark unrest in Northern Ghana—a key swing region. “If we cracked down hard, we risked angering both the traders who fund local campaigns and the communities that rely on them for employment,” he said. “The strategy was to let this slide and deal with it later, maybe after (the elections).”

Even though voters delivered a resounding defeat to the ruling NPP in December 2024, that anticipated “later” has yet to arrive. Yahaya Hamisu, a market vendor in Bolgatanga, shrugs when asked about the new government. “Nothing will change,” he says. “The new government will do the same as the old one. It’s business as usual, all about protecting votes, not protecting the people.”

Mamprusi’s example

In the end, West Mamprusi stands out as an example of what a diligent veterinary service, working with citizens and civil society, can achieve. “Why we have succeeded is that, with the support of (civil society organisation) Brooke Africa, we were able to hold a stakeholder meeting, which resulted in municipal by-laws,” says Alhassan Shehu. Since then, he adds, “there haven’t been any major activities with regards to the slaughtering of donkeys or the exportation of donkey skins” in this district. But the same cannot be said for other parts of the northeast. “These are areas where people consume donkey meat, so it is relatively easy for skin traders to hide under that. The government should pay attention to these areas instead of thinking that all is fine now that Blue Coast is closed down.”

He believes such attention should include Ghana reaffirming the 2016 ECOWAS donkey trade ban nationwide, as well as efforts to coordinate enforcement of the ban across the Police, Immigration, Customs, EPA, and Port Security departments. The government could also support farmers through subsidies, access to markets, or the provision of seed and technical inputs, so they are not forced to sell their donkeys out of desperation. However, progress towards such policies does not yet appear forthcoming.

- The Agricultural Extension Service is a department within Ghana’s Ministry of Food and Agriculture, tasked with disseminating agricultural technologies and information to farmers.

The Donkey Sanctuary commissioned Tiger Eye to investigate the donkey skin trade in Ghana between August and September 2022. Tiger Eye subsequently conducted independent follow-up research.