Thania Petersen places her own body and gaze at the centre of histories long written about her community. Her photographic self-portraits in I Am Royal (2015), made as a gift to her children, gained widespread attention when curator Ingrid Masondo recognised Petersen’s vision and included her work in the Iziko South African National Gallery collection. In this conversation, Petersen reflects on a practice that interrogates the labels of “Cape Malay” and “Coloured” while tracing a creolised sense of belonging across the Cape Flats and the Indian Ocean, through a lens that refuses marginality.

Thembeka Heidi Sincuba: What was it like growing up?

Thania Petersen: I was born in 1980, and my dad went into exile when I was four, so I kind of grew up mainly with my grandparents, and my aunt and uncle on weekends because they would help my grandparents. So, we were always kind of in a state of exile. Even when we were in South Africa. I think everyone was in a state of exile, in a way during apartheid because nobody was where they were meant to be. Everybody was put where they were. There was no choice. So, I think that all the children who grew up in exile, whether literally or metaphorically, our state of mind reflected that.

THS: Did you always know that being an artist was what you were going to do with your life?

TP: Yes. There was never a question of doing anything else. I think once when I was about seven, I watched an episode of Matlock and decided I was going to be a lawyer. It lasted about one episode and then I got over it.

So no, there was never a question about it. I always knew I wanted to be an artist. My family encouraged it. I had the most incredible aunt. If you saw her, she’d look like your typical conservative Muslim auntie from Cape Town, but she was the most interesting, dynamic woman with the most eclectic friends, moving in the most bohemian circles.

Her best friend was a ballerina. She’d take me to the library, to the Baxter Theatre, the Nico Malan Theatre, and to all these whites-only spaces. She’d say let’s just pretend like we belong and she’d put on this funny white accent to make restaurant reservations. Then we’d go to these fancy places, drink Grapetiser and act like we belonged there. She was the most unbelievable influence in my life. She shaped me in so many ways.

THS: What were the first spaces in South Africa to really embrace your work?

TP: The funny thing is the first body of work I made was the I am Royal series, and it was a gift for my kids. It wasn't like I was trying to get into the art world in any way. I was living in Observatory (Obs). I had a shop at the time and a friend of mine, Memory, said to me can you please show another friend of ours, Justin, who was working for Brundyn and he saw the work and the following week he said can we take this to the Cape Town Art Fair. I didn't expect that.

People just took to this work. It immediately got a lot of attention. Iziko National Gallery then contacted me. It was Ingrid Masondo …

THS: I love Ingrid!

TP: Yes, I love Ingrid too. And I was kind of like nobody. I was making work for my kids. Just as a gift for them to better understand who they are. And Ingrid phoned me up and said to me ‘We need to have this in our collection!’ and that is just how it went.

And then Malibongwe (Tyilo) and Sandiso (Ngubane) were like can we throw a party for you at Skattie Celebrates. And so many people came! I was still breastfeeding and since then it just never really stopped. Cape Town and South Africa have been very receptive to my work. People are lovely here. I was just in the Netherlands and (…) I couldn’t wait to get back.

THS: You often use your own body in your work. Is there something rather performative about your practice?

TP: Yeah. I think of my practice as performative. I don't think of my practice as anything else. Like if you had to ask me to describe my practice or put it into a box, I would say its performance. I don't think that as human beings we can fathom the world without performing it. How else do you express yourself as a human being? If you're feeling sad, if you're feeling happy you perform your emotions. You cry, you throw a tantrum. You know, I'm very good at throwing tantrums. Ten out of ten! (laughs) You perform your emotions. Even love is performative. Your love for your children, your husband. The only way to share yourself with the world is to perform.

And so, for me innately, my art is performative. Tunisia made me understand this. I'm obsessed with Sufi dhikrs and music and performance. And in Tunisia, in a place where the landscape is very barren, they have 80 million olive trees or something like that but generally it’s not like something where its lush jungle or anything. It's quite barren in a lot of the places that I went to. So, I think what manifests in civilizations like these is that the art is rooted in performance and in literature and in poetry.

I went to a lot of dhikrs while I was there. It struck me how performative their dhikrs were compared to ours. They would play out exorcisms where they would become possessed and then they would be exorcised and then they would be overcome by good and overcome by evil. When you leave, there's a reinforcement of an understanding of how the world works and it all happens within these religious ritual spaces.

This is fundamentally how we as human beings make sense of the world. We need to perform certain roles and then we understand where we fit into the greater scheme of things. And so, if I have any problem in the world, I first play it out. So, all my work that you see has a theatrical component to it. My photographs are a performance which is staged and photographed. Photographs of a performance. My films are very theatrical. They have backdrops, we perform certain roles, and those films are then translated into textiles. But everything starts with the performance.

THS: There's also a technological element, right? You’ve already mentioned it’s a recorded performance. But I think also performance is a form of technology. Then there’s the photograph, the film, the collage, the design, the textile. All these are technological devices.

TP: Well, yes. I’m always trying to wrap my head around the concept of time. In my latest work, sound is becoming a stronger component. I don’t really work with photography anymore. I do work with it as part of my film, but not as a central medium. And sound, over the past five years, has become a very big part of my practice, because through sound I’m trying to fathom different ways of thinking about time.

And I do think that technology allows you to challenge and express this kind of bizarreness that goes on in your head. Because I don’t think ideas like Afrofuturism, futurism, or science fiction are new. I think they’re ancient.

THS: I wonder if you’d be willing to give us a few tidbits about what you’re currently working on.

TP: I’m not often happy with my work, but this time, I am. I’m happy because I worked hard, and it’s an archive I’ve been building for the past five years. I’ve been collecting music and working with various Sufi communities and groups, including my own in Cape Town, Indonesia, Tunisia, Zanzibar, across these landscapes of Africa and Asia. And the central idea is this: we don’t record sound; sound records us. So how do we decode the sounds to remember who we are? Because I truly believe we suffer from collective amnesia. There’s that poet, her book is Collective Amnesia.

THS: Koleka Putuma.

TP: Yes, exactly. And I believe it’s deliberate. It’s enforced. And of course, with trauma, you lose your memory. Forgetting is a trauma response. So, when you think about that on a communal, continental level, how do we remember? For me, sound has become central to that process. And “dhikr” means “to remember.” So, for me, dhikr is like a memory bank for an entire community, an entire world.

I started collecting and recording these songs, working with different communities. And what’s fascinating is that we all sing the same songs, but the way we sing them tells us who we are. So, in the film, the entire score is composed from this archival music I’ve been gathering and creating. And layered over that are visuals exploring how sound functions as liberation within human existence. Because maybe what we think comes from the past comes from the future.

Maybe these sounds are leading us, not pulling us back. Maybe our ancestors had a closer relationship with the future. That’s why they could build the pyramids, and Great Zimbabwe, and all those other sites aligned with constellations. They understood astronomy and all these seemingly futuristic things that had no fixed time. Maybe they had a language and a relationship with time that was completely different to ours. That’s really what the whole film is about.

THS: What’s it called?

TP: It’s called Jawap—J-A-W-A-P. It’s a Cape word that means “to sing” or “to praise in community.” It’s like an invitation.

THS: Speaking of the future, what comes after Jawap? What are your hopes or manifestations going forward?

TP: Well, now I’m going to start turning the work into textiles. I’m really excited about it. I’ve become obsessed with the idea that we come from communities whose hands literally built the textile industry. After ’94, when we were supposedly liberated, all the white factory owners, once sanctions were lifted, just packed up and closed their factories. That’s why all those buildings in Woodstock are standing empty along the main road. They were all old textile factories. Once they could have everything produced in China and other places for a fraction of the cost, instead of paying us, they closed their factories. In the end, even the lifting of sanctions benefitted them.

Entire communities of beaders, embroiderers, tailors, leatherworkers were left jobless, pushed back to the Cape Flats, left to rot. There was no redistribution, no real transformation. Apartheid supposedly ended, but it didn’t, not in any meaningful way. That's why, for me, working in textiles carries so much importance. I keep coming back to the fact that these are the unspoken realities of what happens when there’s no follow-through. When liberation becomes an idea rather than an action.

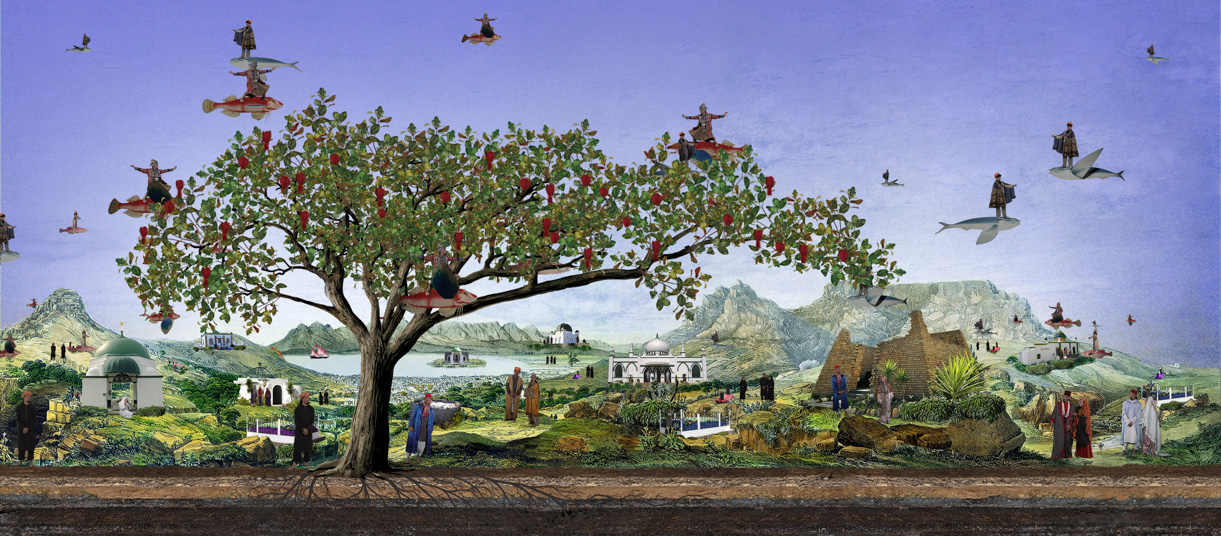

In her work, Thania Petersen turns despair into testimony. Her reflections on the enduring inequalities that shape Black life in South Africa form the ground of her practice. Through photography, film, performance, textiles and installation, she transforms personal and collective grief into acts of visual resistance, showing how history shapes the everyday. Her images are both poetic and political, tracing stolen land, broken promises, and unhealed wounds while insisting on beauty, dignity, and belonging. In holding these contradictions, Petersen’s art becomes mirror and medicine, reminding us that seeing and naming are forms of healing.

ZAM partners with the Thami Mnyele Foundation who hosted Thania Petersen during a short artist’s residency in Amsterdam in October 2025.

Call to Action

ZAM believes that knowledge should be shared globally. Only by bringing multiple perspectives on a story is it possible to make accurate and informed decisions.

And that’s why we don’t have a paywall in place on our site. But we can’t do this without your valuable financial support. Donate to ZAM today and keep our platform free for all. Donate here.